Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear. — Bertrand Russell

On July 29, 1999, Mark Orrin Barton of Stockbridge, Georgia killed 12 people and injured 13 more during an extended shooting spree in Atlanta. The shootings occurred at two separate trading firms a day after Barton bludgeoned his wife and two children at home with a carpenter’s hammer. It is believed that Barton, a day trader in the stock market, was motivated by $105,000 in losses over the previous two months. Four hours after the Atlanta shootings, Barton committed suicide at a gas station in Acworth, Georgia during an attempted escape and subsequent confrontation with police officers.

What are we to make of such impetuous and violent behavior that disrupts the lives of so many in such unexpected ways? It seems that shooting sprees have become commonplace in the news to such an extent that these events are normalized and even expected. One doesn’t have to look further than the 2012 Sandy Hook elementary school shooting and the Aurora, Colorado theater carnage to discover cyclical trends in reactionary destructiveness. Some will point to the vagaries of mental illness and how this acts as a time-sensitive fuse for the inevitability of such violence. Others focus on problems with weapons accessibility and cultural influences for brutality. However, what are the cognitive dynamics that result in such intense moments of high-lethality behavior? Some tragic events appear systematically planned by obsessive individuals preoccupied with revenge, while other instances of extraneous vehemence seem to indicate acute irrational impulsivity accumulated after weeks, months, or years of coping with stress, frustration, and depression (this is distinct from other forms of refractory mental illness, behavior as a result of brain injury, and symptoms of psychosis such as command hallucinations). In a repress/release mode of reactivity, the dynamics of externalized responses to repression and feelings of being out of control could manifest themselves in suicidal or homicidal thoughts to compensate for a compromised sense of agency. Being social animals, the complexity of daily interactions and interpersonal stressors may result in a person feeling threatened in their ability to communicate effectively, function with prosperity, or survive with integrity.

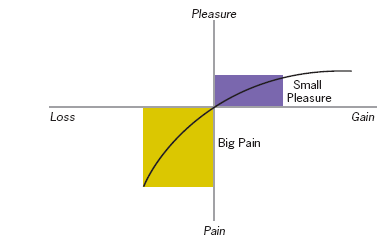

Psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have introduced a concept known as loss aversion that has subsequently been used to understand economics and decision theory (the idea being that people often exhibit a tendency to prefer avoiding losses even more than acquiring gains). This concept may help interpret other types of behaviors that appear impulsive, unusual, or out of character. Some studies suggest that losses of any kind are perceived to be twice as powerful, psychologically, as actual gains. If a person feels threatened or incapable of being in control of certain life variables, there often exists a dominant emotional response (fueled by the sympathetic nervous system, a possibly low-functioning MAOA gene, or aggression-inducing neurotransmitter activity) to redouble one’s efforts in an attempt to compensate for the subjective impact of loss. Even potential or anticipated loss can motivate one to engage in precarious efforts to regain a sense of justice or security. Likewise, suicide, often thought of as an act of “letting go,” could be interpreted as an affirmation and the attempt to regain control with a final response of empowered desperation. Humans have been cognitively conditioned by evolution’s engine of natural selection to avoid pain and move towards positive reinforcement in a variety of contexts. Sometimes, however, even though a person’s ability to biologically survive remains intact, his or her social identity may seem fragmented to such a degree that it feels inexorably damaged. This perception, regardless of its validity, is capable of producing intense emotions of fear and anger that become galvanized and channeled with adverse results because our adrenaline glands are easily capable of overriding the rational judgment and behavioral buffers of the pre-frontal cortex.

How can the intense emotions of loss aversion be avoided? Consistency in communication and expressing oneself through multiple pursuits may help regulate the buildup of negative psychic energy, feelings of helplessness, maladaptive efforts toward escapism, and the anxiety of long-term frustration. As a dynamic system that interacts with a perpetually shifting environment, it’s important to preemptively be aware of our fears and provocations for extreme irritability while focusing on our capacity to adapt in creative ways without succumbing to rigid interpretations of self, attaching our emotional stability to outcomes, or feeling that the interests and mindset of popular culture must dictate our well-being.

What makes us feel irreparably compromised? What makes us feel embarrassingly vulnerable, fearful, and marginalized? What are the necessary values for ensuring a civilized society without the casualties of deprivation, isolation, otherness, and dehumanization? A critical analysis of social constructions, an acknowledgement of interpersonal accountability, and a deeper understanding of loss aversion may illuminate the fragility of human psychology while rethinking what it means to value social sustainability rather than perpetuating the delusion of invincible individualism.

(This article was first published in the NPI newsletter, Spring 2014).

Pingback: In-Security | armchair deductions

Hi mates, its fantastic post regarding tutoringand entirely

explained, keep it up all the time.

Pingback: How to Create a Killer Facebook Ad Design for Your Ecommerce Store | OntheWebIT.com - Website Development and Design

Pingback: How to Create a Killer Facebook Ad Design for Your Ecommerce Store | CoffeeShop Hustle

Pingback: Use the Element of Scarcity As A Marketing Strategy & Tactic

Pingback: ihabexpress.com - إنشاء تصميم إعلان الفيسبوك لمتجرك الإلكتروني

Pingback: What is scarcity marketing and should you use it? - April Ford