Disclaimer: This essay is not intended to characterize all mothers suffering from Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), nor does it suggest that Borderline mothers are inherently responsible for having mental illness. In addition, the following material is not meant to discount the positive outcomes or life lessons that can sometimes occur as a result of being raised by a BPD mother. However, it must be emphasized that Borderline Personality Disorder, also known as Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, is considered one of the most serious and complex mental health conditions in clinical psychology. Like most disorders, considerations should be taken to evaluate levels of functioning and severity on a full spectrum to avoid over-pathologizing or underestimating the psychological disturbance of the sufferer. Unless BPD mothers are in treatment; willing to seek specialized treatment; or willing to admit there’s a problem, they’re not going to be aware that they have a disorder—it’s up to their children, partners, and extended family members to develop this awareness. Generally speaking, BPD mothers are exceptionally resistant to being confronted or challenged, and they will invariably refuse to see themselves as disordered. From their perspective, being disordered implies being defective, “bad,” inadequate, or less than perfect. As long as the mother maintains control of her environment, while hiding behind a fortress of denial, there will be no incentive for cultivating self-awareness or embracing the process of change and potential recovery. Because of her resistance towards self-reflection, she will dismiss, minimize, or rationalize her behavior (deflecting and projecting rather than accepting). In essence, a BPD mother is a psychologically damaged parent “doing her best.” The problematic thoughts and behaviors of a person with Borderline Personality Disorder are not deliberate; they’re automatic. A BPD mother “means well,” according to her distorted perceptions, but she is not well. What needs to be understood are the devastating effects that Borderline mothers can have on their children’s emotional development, mental health, physical health, relationships, and ability to successfully achieve autonomy in adulthood.

No one chooses to suffer from mental illness, and no one chooses their parents. Likewise, no child can be held responsible for their parent’s emotional well-being, they can only offer compassion and work to discover themselves through the filter of time with the courage of honest self-reflection. To be clear, Borderline Personality Disorder is not a premeditated way of being; it’s a psychological predicament. Furthermore, this information is not designed to exculpate adult children of BPD mothers from their own contributions to unsatisfactory life outcomes, but it may offer clarity as to how their behaviors and ways of thinking were formed, influenced, and reinforced in toxic family environments. Borderline mothers don’t know how to interact in relationships, and a relationship with their children is just another type of relationship. Sadly, parental analysis and family of origin issues are generally the last frontiers of discovery for adult children of BPD mothers (children instinctively shy away from objective assessments of their parents out of respect, fear, or because they may feel like a traitor within the family system). Because Borderline Personality Disorder stems from a combination of neurobiological predispositions (genetics) and maladaptive survival mechanisms that were developed to cope with childhood trauma, it’s a condition that’s not suitable for effective parenting or intimate relationships. It’s not about blame; it’s about understanding.

If it’s not one thing, it’s your mother. — Sigmund Freud

In a previous post entitled Chaos and Elucidation: The Borderline Koan, I focused on the clinical challenges and professional liabilities that therapists may encounter when working with an undiagnosed or misdiagnosed patient suffering from Borderline Personality Disorder. More specifically, emphasis was placed on the preemptive identification of BPD in treatment settings, the Vulnerable BPD variety, and what to expect during emotionally charged clinical encounters. Here’s a quick review of the two-tier, conceptual classification system based on non-clinical observational impressions:

Authoritarian BPD Interpersonal disposition: Compulsively self-sufficient, domineering, mesmerizing, intrusive, anxious, irritable, worrisome, dysphoric, demanding, passionate, presumptive, judgmental, perfectionistic, fearful, competitive, impatient, pessimistic, combative, easily angered, petulant, stubborn, critical, paranoid, and envious. Attachment style: Fearful/Preoccupied. Intimacy style: Erotophobic (fearing engulfment more than craving intimacy). Rationale: “I have needs for stability, predictability, and approval that were not met during childhood; therefore, I must be in charge to survive.” Valence: Aggressive, flamboyant, anxious, intense, and irritable. Parenting style: Over-involved. Level of functioning: Moderate to high. Objective: Control of self-image, others, and their environment (overtly expressed).

Vulnerable BPD Interpersonal disposition: Dependent, charming, captivating, coercive, desperate, mercurial, seductive, playful, hapless, passionate, anxious, perfectionistic, dysphoric, duplicitous, suspicious, solipsistic, fearful, affectionate, labile, docile, angry, hypersensitive, desultory, fantasy-prone, childlike, vindictive, self-destructive, and jealous. Attachment style: Disorganized. Intimacy style: Erotophilic (craving intimacy more than fearing engulfment). Rationale: “I have needs for safety, validation, love, and nurturing that were not met during childhood; therefore, I must be taken care of to survive.” Valence: Coy, mischievous, needy, desperate, and enigmatic. Parenting style: Under-involved. Level of functioning: Low to moderate. Objective: Control of self-image, others, and their environment (covertly expressed).

For comparison, the Vulnerable BPD is similar to Theodore Millon’s Discouraged, Self-Destructive, and Impulsive subtypes, whereas the Authoritarian BPD strongly resembles the Petulant subtype. In relation to Christine Ann Lawson’s fairytale archetypes, Vulnerable BPD mothers would align with the “Hermit” and the “Waif,” whereas Authoritarian BPD mothers most closely resemble the “Queen” and the “Witch.” Of course, none of these categories are mutually exclusive, and there’s considerable overlap depending on environmental stressors, interpersonal variables, and social context. Ultimately, every character trait and behavior is on a continuum because BPD is a hybrid disorder that features significant comorbidity with mood disorders, behavioral disorders, and other personality disorders. Subclinical subtypes and colloquial descriptions, such as those incorporated in this essay, are convenient placeholders for purposes of conceptual taxonomy. Nonetheless, assessments of personality disorders in general should incorporate a dimensional model that emphasizes quantitative measurement.

Although Authoritarian BPD mothers can be highly functional and self-sufficient, they’re emotionally dependent. Conversely, Vulnerable BPD mothers tend to be both interpersonally dependent (poor self-efficacy) and emotionally dependent (poor self-regulation). Regardless of differences in presentation, relinquishing emotional dependency is the Borderline mother’s biggest fear because she would be forced to face herself, her past, her insecurities, her mental health challenges, and the comprehensive horror of her underlying pain and despair. In this sense, her fear of abandonment becomes an ancillary phobia, as it portends exposure of the mother’s deeply-rooted dependency issues. Authoritarian BPD mothers were usually parentified as children, whereas Vulnerable BPD mothers were often infantilized. When old enough to become parents themselves, this typology is reversed. In other words, the Authoritarian BPD mother will infantilize her children (mommy controls everything), and the Vulnerable BPD mother will parentify her children (mommy needs pampering). One mother strives to be seen as the “perfect caretaker,” and the other hopes to be “perfectly cared for.” The Authoritarian BPD mother compulsively seeks to do everything for her children, and the Vulnerable BPD mother wants her children to do everything for her. When the bell rings, Authoritarian BPD mothers walk into the ring swinging with a surplus of dominance, tension, and misplaced aggression. Vulnerable BPD mothers, on the other hand, are so fragile that they’re already lying on the floor and begging for assistance that will be used against the paramedics later on. Vulnerable BPD mothers are more likely to be viewed with opprobrium due to parental negligence, whereas Authoritarian BPD mothers are more likely to win Mother of the Year, as presented by a committee of uninformed bystanders, due to their excessive levels of involvement and compulsion for matriarchal supremacy. However, parental overinvolvement is also a form of neglect because it discourages a child’s individuality and invalidates their emotional experiences. Having what is considered an externalizing disorder (external locus of control), Borderline mothers search for external sources of stimulation, validation, and emotional regulation. They also search for external sources of blame to avoid feelings of humiliation and shame. Without the ontological grounding of interiority (a stable sense of self), life, in all of its splendor and terror, must be experienced by acquiring a continuous supply of outside reminders to reassure the Borderline mother that she exists.

In this essay, we’ll be examining the Authoritarian BPD mother (overinvolved and emotionally immature) from the perspective of motherhood; how this disorder affects the mother’s children during development, and the ramifications of long-term exposure caused by interacting with a mentally disordered parent. Authoritarian BPD mothers could be thought of as having an extreme “smothering” or “hovering” parental style (i.e., overprotective, “devouring,” and overbearing) that interferes with their children’s potential for autonomy in the name of love. According to Freud, an Authoritarian BPD mother represents the oedipal mother. Theses types of BPD mothers represent the proverbial “helicopter” parent without a landing pad, and their ability to undermine the growth of their children is boundless. They also incorporate a fairy godmother fantasy defense to justify their need for dominance during family interactions, but the damsel in distress and princess in the tower motifs are also available for situational convenience. Not understanding the comprehensive impact of unresolved trauma on their own psychology, Borderline mothers cannot understand how it affects their children.

People often say that “every family is dysfunctional,” but family of origin problems are disproportionately corrosive whenever children are raised by a Cluster B parent (narcissistic, anti-social, borderline, or histrionic). Children also learn about love and relationships from watching and interacting with their primary caregivers. Virtually every relational interaction that transpires, including the relationship we have with ourselves, is conditioned by our parents during childhood. Most children of Borderline mothers have learned to normalize the abnormal, because the abnormal is all they’ve ever known. Likewise, BPD mothers have unconsciously normalized the abnormal due to their own traumatic childhood experiences. However, mental illness among primary caregivers is not the same as mental illness among siblings and relatives. Proper emotional attunement with one’s biological mother is, arguably, the most influential factor for developmental congruency, self-actualization, and independent success in adulthood. Regrettably, Borderline Personality Disorder is a disorder of the self.

Some of the most common traits of Borderline mothers include the following:

- Fear of abandonment and the perception that others are rejecting or separating from them, whether this is real or imagined. Intolerance of aloneness (autophobia) with recurring dependency issues.

- Having volatile and unstable relationships. The person on the other end of the relationship is either idealized or perceived as malicious, cruel, and uncaring. Posing ultimatums in relationships and searching for attention (validation) and acceptance in social situations.

- A distorted perception of self, commonly manifested as feeling flawed, victimized, or invisible. Lacking a stable identity, which results in deep insecurity, neuroticism, and periods of compensatory grandiosity. Unable to observe and describe one’s own behavior or how it affects others; additional misperceptions of people and events occur while reactions remain self-justified.

- Paranoia, which can last from a few hours to a few days. High levels of stress usually cause paranoid ideation. An overall mistrust of others is common with hypersensitivity to criticism or slights (real or imagined). An inability to discern the complex motivations of others results in preemptive suspicion or vilification. Episodes of transient psychosis during extreme emotional decompensation greatly enhance pre-existing paranoia, delusions, and ideas of reference.

- Impulsive behavior that manifests as impatience and entitlement. Rigidity, disputatiousness, worry, and panic generally precede impulsive actions. Abrupt overreactions are linked to delays in gratification, feeling disrespected, or fears of being separated from loved ones. Impulsivity is exacerbated by low distress tolerance, fear, and a hypercompetitive need for control.

- Rapid mood swings based on interpersonal triggers. A person with BPD may experience euphoria, sadness, anger, guilt, anxiety, shame, despair, or panic all within a few hours (hyperemotionality). Psychosomatic manifestations of emotional instability can include muscle tension, fibromyalgia, ulcerative colitis, IBS, hypertension, dermatologic disorders, eating disorders, body dysmorphia, hypochondriasis, and insomnia. The BPD’s anxiety and obsessive need for control takes its toll on the body through conversion-based somatization disorders.

- Feelings of numbness or emptiness. Easily bored with a need to stay busy. Socially awkward, unsettled, worried, tense, moody, and insecure. Unable to self-regulate moods, emotions, and self-esteem without external stimulation (reassurance, recognition, and/or contact comfort).

- Intense feelings of anger or rage. Inappropriate and often extreme emotional reactions to disappointment, separation, or imagined threats. Loss of temper, which can be accompanied by verbal or physical aggression. Antagonistic, critical, and judgmental with unrealistic expectations of others (uncompromising). Deploying the passive-aggressive “silent treatment” after contentious encounters and rarely apologizing, admitting fault, or accepting accountability for behavior.

- Dichotomous thinking (black & white interpretations of reality and “splitting”). Situations and people are bifurcated into “good” or “bad” categories to reduce ambiguity and anxiety. Other people become enemies or allies. Stressful or challenging situations are filtered through a negativistic, egocentric, and emotionally reactive lens (adversity is the equivalent of a personal threat). Poor or non-existent conflict negotiation skills. A preference for simplicity, certainty, and zero-sum transactional approaches (all or nothing) during most interpersonal encounters due to adaptive inflexibility. Pars pro toto assessment style when it comes to making sense of other people’s actions.

- Emotionally immature (arrested psychological development). Often thinks like a child (chronic irrationality) and displays infantile behaviors during periods of euphoria or stress (frisky, coy, charismatic, despondent, impulsive, angry, or petulant). Vivacious when appeased, but pugnacious when displeased. Cannot tolerate challenging emotional confrontations and resorts to projection, denial, detachment, dissociation, temper tantrums, or rage. People with this disorder are often described as children in adult bodies.

As noted in the classification section, there exists two basic parenting styles among Borderline mothers: Overinvolved and under-involved. But these polarized approaches to parenting can temporarily switch according to various changes in the Borderline mother’s mood while exacerbated by splitting and passive-aggressive behavior. For both Vulnerable and Authoritarian BPD mothers, an inability to regulate conflicting emotions during stressful interactions creates havoc for other family members as they try to interpret and effectively respond to such perplexing, contradictory, and unpredictable dynamics. Borderline mothers are infamously known for being erratic, dramatic, and emotionally volatile. BPD mothers are also known for choosing either narcissistic or passive/codependent partners, but many end up living alone because of recurring marital, romantic, and interpersonal conflict. BPD mothers are intense and exert a persuasive hold on their children’s feelings (emotional incest). This dynamic occurs when a child feels responsible for attending to their mother’s emotional well-being; it also occurs when the mother cannot get her emotional needs met by her spouse or other adults. In tandem, the mother’s children will feel obligated to predict, interpret, and appropriately respond to their mother’s conflicting feelings, thoughts, and needs.

What’s all of this “need” about? The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan emphasized the concept of “lack” as a powerful motivation for human behavior. And, to be sure, the Borderline mother is lacking in crucial developmental features due to various forms of childhood deprivation that produce cognitive deficits affecting her emotions and ability to relate to self or others (object relations). In essence, developmental deficits from a bygone era transmogrify into relational deficits that adversely affect the mother’s interactions with others. To compensate for these deficits (missing internal regulatory mechanisms), she desperately seeks someone who is willing to provide a simulacrum of these ingredients (essential ego functions) so that she can feel whole and secure. By latching onto someone, her unconscious hope is that they will become a stable, safe, and soothing introject. The problem is that her brain’s way of healing itself is by obtaining exogenous (external) remedies for endogenous (internal) deficiencies instead of facing her fears and committing to the psychologically painful work necessary to acquire introspection and emotional self-sufficiency. In other words, the Borderline mother outsources her regulatory needs to offset instability with the additional hope of fulfilling archaic loose ends from a childhood gone awry. Subsequently, the mother is motivated by her deficiencies and her longings are expressed in a unique array of maladaptive behaviors. Furthermore, alterity (individuation) makes her nervous because it provokes separation insecurity, which makes her feel abandoned and unsafe. Her identity is diffuse because her core is empty, so she becomes a huntress on an insatiable mission to fill the void. As a consequence, the person (aka “favorite person” or intimate other) she unconsciously “uses” to achieve course correction either implodes under the weight of her endless needs or they withdraw because they finally realize the importance of their own survival. Without being able to objectively evaluate her thoughts, feelings, and behavior, the Borderline mother is oblivious to the insidious effects her actions have on others. Overall, her most cherished supporters become collateral damage in the wake of her neediness, anxiety, panic, paranoia, and anger. To psychologically fuse with a partner, spouse, or child is a life-or-death imperative for the BPD mother, but it eventually results in the paralysis of potential for all participants in her path. Borderline mothers do not intend to behave as they do, but they do intend to get their needs met by all means necessary. Whenever denied, frustration is converted into aggression as a method to achieve control. Consequently, the Borderline mother cannot relate to her children as they are; she can only identify with them to the extent that they’re capable of serving the exigencies of her residual deficits. As if all of this wasn’t daunting enough, the Borderline mother’s lack of object constancy (the ability to maintain a consistent bond with others, despite fluctuating circumstances and emotional states) signifies that she will expect frequent contact to temporarily assuage her inner turmoil.

Borderlines have an uncanny ability to notice specific details about other people, but they lack insight when it comes to their own behaviors or how others perceive them (an understanding of the impact they have on others is conspicuously absent from the Cluster B modus operandi). It cannot be emphasized enough that people with BPD know only too well how other people are affecting their emotions, but they cannot comprehend how their behavior affects others. The Borderline’s interpersonal awareness is vigilant, but it’s filtered through a distorted lens of mistrust, beset by frequent misinterpretations regarding the intentions of others. BPD mothers can ostensibly recognize the hardships of their children, but they cannot authentically connect because of their own anxious preoccupations and compromised theory of mind. In addition, Borderline mothers compulsively seek advice due to impaired reality testing while simultaneously defaulting towards their own brand of maladaptive self-determination. A Borderline mother’s capacity for empathy, although high in emotional sensitivity, is self-oriented, and she experiences exceptional difficulty with cognitive empathy (empathic accuracy). Whenever her immediate needs are frustrated, consideration for others is often the first thing that goes out the window. Simply put, she cannot understand the perspective of others, especially in the heat of her most current crisis. An inability to see other people as stable, individuated, and integrated human beings (whole object relations) is paramount to understanding the Borderline mindset. It’s the mindset of trauma, and trauma cannot get outside of itself. Deficits in mentalization (reflective functioning) interfere with the Borderline mother’s ability to accurately perceive other people or to form realistic impressions. As a result, there’s a significant gap when it comes to understanding the emotions, thoughts, and intentions of others. Unable to integrate positive and negative aspects of herself, she’s unable to do so with others, thus dichotomizing people into gratifying or frustrating objects (“good” or “bad”). Such rigid evaluations are bereft of nuance and complexity, hence she is always interacting with a “distorted other,” which aggravates her innate apprehension. The Borderline mother is afraid of the individualism, maturity, and agency of those around her because autonomy represents unpredictability. Consequently, fear becomes her GPS because she may not be able to control what others think about her or what they might do in her presence (i.e., disappoint, reject, hurt, humiliate, or take advantage of her). She is dubious and always testing the waters. Her way of coping with potential “stranger danger” is to either push people away or pull them into her narrow psychological jurisdiction.

For her children, the mother’s attempts to relate may feel superficial or insincere because people with BPD have problems with differentiated relatedness. Borderlines can often identify the emotional states of others via mental state discrimination, but they have difficulty interpreting them in a non-personal way due to self-referential hypersensitivity, which includes paranoia and catastrophizing. BPD solipsism will ultimately override any concern for the needs, challenges, and limitations of others. In reality, the Borderline mother feels engulfed by the emotional needs of others because her own are insurmountable. Internally mismanaged by a combination of insufficient mentalization and alexithymia, she cannot understand the intense nature of her own emotions, let alone comprehend the complex emotional experiences of her children. Emotionally speaking, the Borderline mother cannot stand on her own two feet. As a consequence, her children become representational objects who are expected to support their mother’s unending psychosocial dilemmas. In a fundamental sense, the children of a Borderline mother are instrumentalized to serve her needs. Minimizing ambiguity reduces fear, so it’s easier for the mother to invalidate her children’s emotional experiences and personal struggles rather than being overwhelmed by their complexity. She is, after all, consistently overwhelmed by her own emotions (aka the “dead mother” complex) and was invalidated herself while growing up. The mother’s priority is, paradoxically, to rely on her children for stability, security, reassurance, validation, and emotional comfort. As a result, her children become involuntary enablers via psychological fusion during a codependent process of incremental enmeshment. In other words, the children unwittingly fulfill important psychological functions for their mother by becoming her external regulators, crisis attendants, guardians, and “redeemers.” Overall, they become their mother’s recharging station to generate feelings of safety, self-esteem, and selfhood that she cannot produce for herself. Despite the crucial role her children play as representational objects, they also become objects of frustration because they remind the mother of her own childhood, fears, developmental lacunas, and innate vulnerabilities.

Along the contours of the Karpman drama triangle, the BPD mother (self-identified victim) has a tabloid-worthy issue with something or someone (persecutor), and her children (rescuers) are implicitly or explicitly expected to support her grievances while making intrepid efforts to “fix” her problems. She comes across like a bewildered and agitated project manager who insists that others agree with her blueprint of never-ending complications and commit to doing her bidding according to her shifting expectations. Sadly, these problems are seldom resolved in a way that’s considered satisfactory to the mother; ergo, the victim-persecutor-rescuer cycle continues or intensifies as new complications emerge (having a persecutory object justifies continued dependency, and a great deal of time is spent chasing imaginary demons). Throughout this dynamic, the children begin to identify as crisis attendants while their mother resolutely identifies with the drama of each crisis. The pressure to merge with the velocity of her emergencies is profuse. Slowly but surely, her children begin to feel confused, anxious, and inadequate about their ability to effectively manage future predicaments. While their confidence for handling these situations erodes, a theme of trepidation, incompetence, self-doubt, negativity, and failure will affect other endeavors as they grow older.

Regrettably, the image of motherhood is more important to BPD mothers than the mechanics of effective parenting. What reflects well on the mother is usually prioritized over what’s beneficial for the child. Since most Borderlines were raised in abusive and invalidating environments, they’re unable to give to their children what they never received. People with BPD typically experienced life in a chaotic household with emotionally negligent, disruptive, or physically abusive parents who also suffered from personality disorders or other forms of mental illness. Subsequently, the survival mechanisms that the helpless little girl developed to cope with childhood trauma are reflexively incorporated into maladaptive ways of thinking and behaving whenever she leaves home to establish her own family. These primitive defense mechanisms may have been useful for protecting a traumatized and hypersensitive child, but they invariably outlive their usefulness in adulthood. Regardless of its immediate survival value, fear conditioning does not bode well for optimizing human flourishing over time. The Borderline’s fight-or-flight response never turns off because they’re forever fractured by trauma and operating in self-preservation mode. Ironically, the BPD mother recreates in her nuclear family the very toxic conditions that she tried to escape from when she was a child. She may also try to establish the “perfect” domestic atmosphere of her imagination that often feels restrained, eerie, forced, and artificial. In essence, the psychological pain that she cannot face from her past reanimates itself in the present as she attempts to gain mastery over unresolved conflicts. Subsequently, the trauma bond that the mother experienced with her parents is reestablished with her children, as they become unwitting participants in a theatrical revival by receiving a bootleg version of their mother’s upbringing. It’s an experiential palindrome that resembles phantom limb syndrome; the original source of pain has subsided but the residual damage is recycled in the present. Since her most abusive parent maintained power within the family unit, the Borderline mother learned to covet the bully. She also craved love and attention from a parent or parents whom she feared (disorganized attachment). Because love and fear cannot exist in the same space, she disappeared into the fragmented wasteland of structural dissociation. This pathological system of tragic embodiment and traumatic interrelatedness continues because the BPD mother personally identifies with abuse, instability, victimization, and impending doom (most borderlines were victims of narcissistic abuse who become unconscious purveyors of narcissistic abuse). In other words, she checked out a long time ago and her body is on autopilot. More succinctly, the mother who runs the home is not at home.

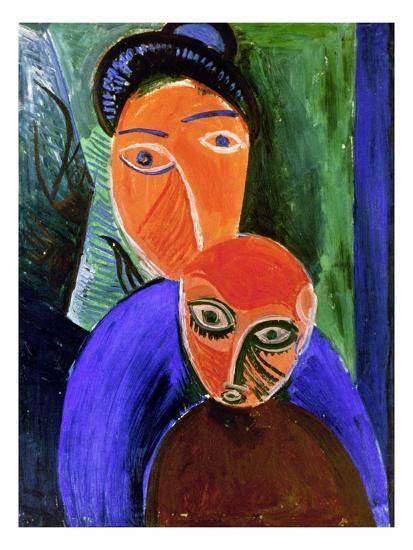

As Christine Ann Lawson stated in Understanding the Borderline Mother, “Chronic psychological degradation of a child, or an adult, can have deadly consequences.” Fear, paranoia, panic, impulsivity, confusion, irritability, anger, and a constant need for reassurance to avoid feelings of abandonment (severe separation anxiety) are the hallmarks of an anxious child who never developed a secure attachment to a reliable caregiver during the first few years of life. Accordingly, the BPD mother is living in a state of eternal recurrence with “the world is against me and it’s your job to recognize my suffering” mentality (unrelenting crisis). It’s the portrait of an insufferable sufferer. As the painting suggests, she’s the embodiment of emptiness and fear because she was neglected, rejected, or physically abused by her original caregivers. Although the Borderline mother’s grievances may appear proximal, they’re invariably stemming from distal wounds. Furthermore, honest expression of feelings and self-exploration were either prohibited when she was growing up or seen as a weaknesses, so she maintains this repressive motif through a combination of dissociation and denial to avoid further feelings of shame. As she continues to bewail the loss of her youth without satisfactory solace, she invites her children to share in the travails of her reverberating misfortune. Consequently, BPD mothers fear the prospect of meaningful change because change symbolizes the unpredictability of their childhood and reminds them of not being in control. Receiving mixed messages from abusive or emotionally unavailable parents translated into assuming mixed messages from others, thus setting the stage for the mother’s paranoid ideation, approach-avoidance attachment style, passive-aggressive behavior, and repetition compulsion. There’s a war going on inside her head and no safe space can be found. The mother feels as if she’s always being acted upon, even when she’s acting out, and her hypervigilant survival tempo will always be prioritized over slowing down enough to initiate the arduous process of self-analysis.

Borderline mothers often grew up in a state of extreme emotional deprivation, so they will spend the rest of their lives trying to compensate for various developmental and attachment deficits. However, their method of obsessive-compulsive overcompensation (anankastia) causes lifelong relationship problems with just about everyone they get close to. To make matters worse, the Borderline mother unconsciously seeks psychological equilibrium at the expense of her children and significant others. Because unresolved trauma keeps the Borderline mother in a state of arrested development, she’s essentially a mommy who needs a mommy and a child trying to raise children of her own. The Authoritarian BPD mother, in particular, is overprotective to a fault because she’s symbolically protecting herself.

From the FOG website: I have been emotionally wounded and crippled by my early life experience, from which I have never healed. The pain and neurotic anxiety drive me to live vicariously through my children. I somehow believe that if I can keep them under my control, the scared little girl that lives within me will at last feel safe and protected. I am putting my emotional needs ahead of my children’s developmental needs, and on some level I know this. I can’t stop because I’m addicted to the soothing feeling of reassurance that having control provides.

Simply put, what happens in childhood does not stay in childhood.

Children of Borderline mothers are also at high risk for developing BPD, or some other personality disorder, due to strong hereditary and intergenerational influences. Others may try to model their mother’s behavior until they realize that it’s abnormal, unsustainable, ego-dystonic, and profoundly unhealthy. More often, children become collateral damage in the wake of their mother’s overwhelming desire for control and enmeshment, which results in succumbing to various mental health problems while spinning their wheels when it comes to self-determination. As the child’s need for healthy exploration is stifled by their mother’s need for control, so is the child’s capacity for developing independence in adolescence and early adulthood as the umbilical cord becomes a leash. The emotional neglect, drama, and abuse that the mother endured during childhood is unconsciously reenacted in her intimate relationships and approaches to parenting (i.e., poor communication, feelings of victimization, interpersonal conflict, psychological projection, explosive anger, emotional reasoning, controlling behaviors, and overreactions to perceived slights or threats). *Some BPD mothers experience transient psychosis or engage in suicidal behavior during periods of extreme emotional decompensation. Although the BPD mother may feel and fervently believe that she is nothing like her parents, she has unknowingly internalized faulty perceptions and behaviors from enduring adverse conditions during childhood. The chaos of the Borderline’s mindset is later projected onto their surroundings because they see the environment as a canvas to capture and reflect their inner suffering. In other words, “my pain must be painted everywhere to verify that my suffering is not in vain.” Subsequently, the mother’s feelings become facts (psychic equivalence), and she externalizes causation. It’s a theatrical cry for help, but meaningful assistance meant to elicit qualitative change and insight will undoubtedly be met with defiance because the source of her misery is seen as peripheral. Likewise, children of BPD mothers may subconsciously mirror or endorse their mother’s values, beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes through projective identification, which can result in exaggerated overidentification (many of the mother’s maladaptive coping skills for managing stress are inherited or modeled by her offspring). By introjecting their mother’s tension-infused and paranoid worldview, her children will receive validation and support, but they ultimately sacrifice their own sense of identity through the maintenance of an unhealthy alliance. Without developing a robust sense of independence, a pattern of codependency typically ensues, which includes low self-esteem, a strong need to please others (fawning response), feeling responsible for other people’s problems, and difficulty setting boundaries. Codependent behavior is linked to having parents who ignore their children’s needs, parents with narcissism or other personality disorders, controlling or overprotective parents, and parents who resort to bullying when challenged or frustrated. Conceptually speaking, the “speed of need” represents the BPD mother’s core dependency issues and the “speed to accede” captures her children’s propensity for codependency.

“Mothers with BPD tend to give feedback and validation to their children largely based on whether or not the child pleases the parent rather than objective feedback. They define the self-worth of the child based on the ability to please others and hence encourage them to build an identity around being a people pleaser. This is an unhealthy form of selflessness that compromises the child’s self-confidence,” states Daniel S. Lobel, Ph.D.

Trauma bonding (aka betrayal bonding), a term coined by Dr. Patrick Carnes, occurs when a person experiencing physical or psychological abuse develops an unhealthy attachment to their abuser through intermittent positive reinforcement. Untreated people with BPD automatically lay the groundwork for contentious dynamics because they suffer from a relational disorder that demands too much accommodation from significant others. Without being able to respect the personal space of loved ones, mothers who suffer from this disorder will cause their children to suffer. Although unintentional, a BPD mother’s primary intention is to get her needs met, and this places an unsustainable burden on her children. The children may rationalize or defend abusive behavior; feel the need to maintain loyalty; isolate from others, or hope that their abuser’s behavior will change. Because there’s always some payoff for staying bonded to a Borderline mother, occasional rewards (psychological or material) will discourage thoughts of “betrayal,” which is really nothing more than healthy maturation. Not allowing her children to separate, the Borderline mother hinders individuation and promulgates emotional incest during infancy, adolescence, and adulthood. Over time, the mother’s children become the equivalent of codependent zombies; sequacious, obsequious, and anxiously awaiting their next set of instructions (the Norman Bates effect). Disagreement with the values, feelings, and beliefs of a Borderline mother is not an option, and she will invariably get her way in the end.

The following are commonalities in parenting behaviors that typify mothers with Borderline Personality Disorder: (1) they use insensitive forms of communication; (2) are critical and intrusive; (3) use frightening comments and behavioral displays (Hobson et al., 2009); (4) demonstrate role confusion with offspring (Feldman et al., 1995); (5) inappropriately encourage offspring to adopt the parental role (Feldman et al., 1995); (6) put offspring in the role of “friend” or “confidant” (Feldman et al., 1995); (7) report high levels of distress as parents; (Macfie, Fitzpatrick, Rivas, & Cox, 2008); and (8) may turn abusive out of frustration and become despondent (Hobson et al., 2009; Stepp et al., 2012).

In a research article entitled The link between personality disorder and parenting behaviors: A systematic review: “The links between personality disorder, attachment insecurity and child maltreatment identified in the literature above goes some way to help explain the frequently observed intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment (Pears & Capaldi, 2001). Parents with personality disorder may be particularly vulnerable to treating their children in the same way that they themselves were treated. Indeed, Adshead (2003) claims that the children of personality disordered parents may be placed at risk of physical and emotional harm as a consequence of the emotional difficulties, dysregulated affect, hostility, unusual cognitions and preoccupation with the self that characterize aspects of personality disorder. Cordess (2003) more specifically asserts, that different personality disorder subtypes are likely to (negatively) impact on parenting in specific ways. In a review specifically relating to the children of mothers with Borderline Personality Disorder, Lamont (2006) identifies these children as disadvantaged and at high risk of future psychopathology as a direct consequence of their mothers’ borderline symptomatology.” To make matters worse, stress hormones, which are notably higher among Borderline mothers, are passed through the placenta to shape the brain and nervous system of their offspring, which causes their children to become even more susceptible to the interpersonal vagaries of their mother’s pathology after birth. Because mothers with BPD have difficulty coping with stress (low distress tolerance), their mere presence acts a chronic psychosocial stressor for their children.

15 signs of toxic parenting, as compiled by Dr. Sharon Martin, include the following:

- Self-centered and have a limited capacity for empathy: They always put their own needs first and don’t consider other people’s needs or feelings. They don’t think about how their behavior impacts others and they have a hard time understanding how other people feel.

- Disrespectful: They fail to treat you with even a basic level of respect, courtesy, and kindness.

- Emotionally reactive: Toxic parents often have difficulty controlling their emotions. They overreact, are “dramatic”, or are unpredictable.

- Controlling: They want to tell you what to do, when to do it, and how to do it. Toxic parents always want to have the upper hand. Guilt and money are common ways they exert power and control.

- Angry: They’re harsh and aggressive. Or they might be passive-aggressive – using the silent treatment, snide comments said under their breath, or intentionally forgetting.

- Critical: Nothing you do is ever good enough for a toxic parent. They find fault with everything.

- Manipulative: They twist the truth to make themselves look good. They use guilt, denial, and trivializing to get what they want.

- Blaming: They don’t take responsibility for their own behavior, won’t own their part in the family dysfunction, and blame it all on you (or another scapegoat).

- Demanding: They expect you to drop everything to tend to their needs. Again, they have no concern for you, your schedule, or your needs; it’s all about them and what you can do to serve them.

- Embarrassing: They behave so poorly that you’re embarrassed to be associated with them.

- Cruel: Toxic parents do and say things that are downright mean. They mock you, call you names, point out your shortcomings and intentionally bring up things that you’re sensitive about.

- Boundaryless: They intrude on your personal space and don’t accept that you’re a grown adult who is completely separate from them. They want to know about your personal life, they stand in your personal space, come over uninvited, and offer unsolicited advice.

- Enmeshed: Your parents have an unhealthy reliance on you. They share too much personal information with you and rely on you to be their primary source of emotional support.

- Competitive: Not only do they always need to be right, they act like they’re in competition with you. So, instead of cheering you on and being happy for your successes, they try to one-up you, diminish your accomplishments, or ignore you.

- You feel bad when you talk to, spend time with, or think about them: You feel worse after an encounter with your parents. You dread talking to them. And even the thought of your toxic parents can cause your body to tense up and your stomach to churn. Painful memories may surface. Their negative energy taints everything they touch. If you have toxic parents, you probably weren’t encouraged to have your own feelings, so you might not be used to noticing them. So, be sure to pay attention to your feelings and notice whether your parents trigger feelings of anger, sadness, guilt, shame, or other negative emotions.

Unfortunately, children and adult children of Borderline mothers often succumb to problems with low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, PTSD, compromised identity, addiction, age regression, hypervigilance, derealization, depersonalization, obsessive-compulsive behavior, addiction, escapism, defensive posturing, rebellion, rumination, emotional repression, sexual repression, confusion, apathy, procrastination, perfectionism, chronic fatigue, despair, negativity, stress-related illnesses, self-hatred, and suicidal ideation. *Many children and adolescents with noted behavioral problems are often reacting to the effects of living with a mentally ill parent or being raised in an invalidating/chaotic environment. Adult children of BPD mothers are also more susceptible to being involved with high-conflict or pathological relationships through programmed familiarity (operant conditioning via insecure attachments) that result in conflating love with trauma bonding, which unconsciously associates nurturing with abuse. Ultimately, compulsive attempts to assuage or win the approval of others becomes more important than believing in oneself. However, some adult children of BPD mothers resign themselves to permanent isolation due to chronic self-doubt, feelings of unworthiness, hopelessness, and recurring fears of inadequacy. A conspicuous lack of self-respect while distrusting one’s intuition outlines the child’s concept of self as they enter adulthood; perpetuated by a fatalistic belief system (internalized bad object). Other traits that emerge among children of Borderline mothers include excessive rumination, self-criticism, inhibition, and a negative (pessimistic) attributional style. Worst of all, children of BPD mothers often fail to achieve autonomy, which results in lifelong problems with insecurity and feeling as if they have been “left out” of the adult world. Ultimately, there’s a failure to launch, or a failure to launch correctly.

Since the BPD mother has a monopoly on Weltanschauung, suffering, and a competitive need for supremacy, her children may grow up feeling helpless, guilty, or ashamed for trying to assert or express themselves. Because these children have learned to mistrust their intuitions, they’re usually convinced that the problem must be with them instead of their mother or the family system. Subsequently, the children often end up with the exact same mindset as their mother (i.e., feelings of unworthiness, fear, and insecurity) as they internalize a large arsenal of negative beliefs about themselves and others. For example, daughters of Borderline mothers frequently report feelings of shame and sons of Borderline mothers often report feelings of being emasculated. An overwhelming fear of vulnerability contaminates the children’s relational potential as safety and suppression are chosen over exploration. When mounting frustrations finally breach the levee, a flood of depression, anxiety, and despair inundate the children’s psychological landscape. If the children are lucky enough to escape the impact of family chaos by early adulthood, they may continue to live in a state of vicarious suppression and unconsciously deny themselves the freedom of psychological separation. Essentially, the mother’s emotional dysregulation fosters developmental dysregulation in her children, and her shame is sponsored by proxy. Inconsistencies in parenting are a force multiplier for creating inconsistencies in a child’s ability to acquire self-esteem or manage their own lives as they get older. Sometimes these delays in childhood development are overcome in adulthood through experiential contrast, therapy, healthy relationships, career involvement, and the establishment of adequate spatial and emotional distance from the BPD mother. More often, these children remain in the dark; become disillusioned; continue to suppress their emotions; experience low levels of confidence; embrace futility; resort to self-sabotage, and eventually wonder what in the hell went wrong.

The stress of parenting causes Borderline mothers to disregard healthy discipline that promotes growth, independence, and self-respect in favor of various forms of abuse that foster inhibition, confusion, shame, humiliation, insecurity, and fear (abuse that was normalized during the mother’s upbringing). However, BPD mothers don’t think of themselves as abusive, because their combative behavior is a natural byproduct of their disorder (misplaced aggression); besides, it’s all they’ve ever known (ego-syntonic rationalizations for ego-dystonic emotional states). In other words, all thoughts, feelings, and actions are self-justified. Psychological abuse through emotional neglect, verbal attacks, criticism, mocking, “smothering,” and/or physical abuse enacted by draconian methods of punishment are the methods of choice for BPD mothers when raising (aka controlling) their children (people with BPD gain an unusual amount of psychological satisfaction from enacting punishments via their adherence to the talionic impulse). In addition, the mother’s impulsivity, if not recognized in other behaviors, will typically manifest in her reflexive need for control, which rapidly impinges on the space of others. But whenever her children become adults, the mother’s need for control will likely manifest along surreptitious delivery systems (e.g., financial control, compelling ultimatums, “emergencies,” or unreasonable demands for attention and proximity that appear reasonable). In such cases, children may feel intimidated or annoyed by their mother’s intrusiveness and neediness while simultaneously feeling obligated to acquiesce for the sake of comity. Furthermore, children of the disordered frequently question their own sanity, as their mother assumes absolute authority concerning the nature of reality.

BPD mothers see their children as extensions of themselves, or much needed parts of the self (need-gratifying objects), to stabilize their emotions and provide a sense of identity. After all, the role of being a mother provides some degree of identity fulfillment. Unfortunately, the Borderline mother relies too much on her children for purposes of commiseration and reassurance, which turns the mother-child relationship into an indispensable support structure for a clinging parent. Her dependency needs are counterintuitive and often misunderstood because she exhibits unparalleled levels of hardheadedness, stamina, and determination. The Authoritarian BPD mother can also be giving and empathic at times, only to exhibit extreme selfishness when her fear of engulfment takes over. She may also alternate between denying herself (emotional anorexia) and excessively pampering herself (sensation-seeking). To survive, she developed a split-self that is both counter-dependent (“I cannot rely on anyone”) and emotionally dependent (“I cannot live without someone who makes me feel safe”). In other words, she is fiercely self-sufficient but also needy and scared. She is unfathomably lonely but her high-functioning ability to fill the void provides an ephemeral reprieve from the howling abyss. She is drowning but swimming so furiously that she doesn’t have time to notice how far she has drifted from shore, or how far she has dragged her children out to sea. Control keeps the mother from feeling vulnerable but she also leverages her vulnerability to acquire emotional support. Furthermore, an Authoritarian BPD mother’s need for dominance creates an Animus possession (masculine tyrant persona) to ensure capitulation to her needs. Without self-compassion, she cannot muster compassion for what she puts her children through to avoid virtual disintegration. What transpires is a BPD brand of pissed-off dependency, protected by a firewall of indefatigable irrationality. Love becomes a conditional possession for the BPD mother, but her children are repeatedly subjected to tests and confirmations to prove unconditional love for their mother, with the not-so-subtle implication that separation equals betrayal. Because of the mother’s unrivaled need for control to avoid feelings of abandonment, her children will invariably feel obligated to serve as their mother’s emotional wet nurse, surrogate partner, surrogate parent, best friend (aka favorite person), confidant, savior, apologist, negative advocate, object constancy regulator, blame container, safety provider, therapist, or consigliere. However, the enormous pressure placed on any child to fulfill such unrealistic and unsustainable roles will eventually result in a codependent relationship that’s emotionally exhausting, confusing, and disturbingly counterproductive. Subsequently, there will be nothing left when it comes to the children’s emotional needs and essential requirements for personal growth. The underlying message is that independence is a rejection of the mother and justification for her to criticize or reject the child. This dilemma places a great amount of obligational stress on the children to be available for their mother instead of themselves. Consequently, manufactured divisions among siblings may include the “hero child,” the “scapegoat child,” the “golden child,” and the “caretaker child.” These narrowly defined roles often become self-fulfilling prophecies in pathogenic families. Instead of having a broad range of independent qualities that contribute to and encourage the formation of a healthy family unit, the children become typecast members of a disorganized pedigree with low levels of family cohesion.

Borderline mothers employ a combination of fear, obligation, and guilt (FOG) to ensure that their children remain loyal and continually invested in their inconsolable emotional needs. However, the mother’s desperate search for stability, ironically, results in more instability. Because of the mother’s intolerance of being alone (autophobia), her children may feel compelled to rescue her from drowning in sadness, uncertainty, loneliness, and worry. Borderline mothers are caregivers who need caregivers, so their unmet needs remain counterintuitive. In many cases, her children provide an opportunity for the mother to establish a corrective relationship as compensation for a lifetime of insecure attachments. In fact, this is why BPD mothers often perceive their children’s friends or romantic partners as potential sources of competition who inconveniently take away from her need for attention, affection, resources, and dominance. In other circumstances, the mother may engage in inappropriate conversations or interactions with her children’s friends or come across like the mom who acts like a teenager. The ultimate desire to isolate her children from the influence of diverse socialization allows the BPD mother to feel in control of family commitments while avoiding feelings of separation insecurity (additional power is achieved through restrictive control of resources and outside activities). To maintain an in-group/out-group mentality solidifies an “us versus them” climate of fear that promotes mutual dependencies, ushered in by the mother’s black & white thinking. Ironically, the mother may even compete with her own children, or become visibly envious, as if they were rivals who must be subdued and defeated (narcissistic rivalry results in dysphoria when others succeed and elation when others fail). In some cases, her envy can become so virulent that it extends to being envious of her children’s accomplishments, material possessions, happiness, relationships, and stability.

Regarding overlapping traits of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), the BPD mother’s compensatory grandiosity is exposed through her sense of entitlement, interpretive infallibility, paranoia, psychic equivalence, and fantasies of omnipotence, especially during periods of emotional decompensation. Although BPD and NPD comorbidity is possible (some studies suggest up to 40%), an untreated Borderline mother is already the reification of “main character syndrome,” so extra solipsism need not apply. For people with BPD and NPD alike, life is seen as a competition for external validation, but the methods and reasons for attaining this fleeting commodity vary according to the seeker. When it comes to the Borderline mother, her children must act as a mirror to reflect her inflated self-image while counterbalancing how deflated she really feels whenever the curtain is lifted. In this sense, narcissistic defenses protect against negative affectivity. To reduce the agony of her inner turmoil, she doubles down on her weaponry of passive-aggressive behaviors and outright viciousness. For example, to be the adjudicator of other people through binary assessments is profoundly narcissistic, regardless of the mental deficit that makes dichotomous thinking prevalent (poor object relations). Likewise, judging others based on how they affect one’s feelings during any given moment is the height of self-absorption. As noted in Chaos and Elucidation: “Ironically, some people with BPD will accuse anyone who isn’t focusing on them of narcissism, especially if there’s a diminution of appeasement from their favorite person.” The mother sees herself as sui generis, but her theatrical posturing and ostentatious declarations are imbued with crushing insecurity that fully reveals itself under stress. She prefers gossip and virtue signaling when faced with the challenges of complex social interactions and resentment is always lurking in the shadows, enveloped by an ongoing persecution complex that provides her with a sense of meaning in the face of uncontrollable variables. To be the subject of persecution is to be special, and being special demands special consideration from others. For the most part, rejection sensitivity aggravates narcissistic and antisocial behavior in people with BPD, and the expression of these traits is generally contingent on the severity of their reactivity during periods of emotional decompensation. Nonetheless, Borderline mothers continually compare themselves with others and unknowingly influence their children to doubt themselves by default. When the mother repeatedly compares her children’s upbringing with her own upbringing, or compares her success with her children’s success, this only demonstrates the persistence of her unresolved internal conflicts. Healthy parents do not compare themselves with their children, but Borderline mothers see life as a competition that they must win at all costs. Subsequently, the children’s need to believe in themselves is overshadowed by the belief that their existence is integral to their mother’s capricious emotional needs. Afraid of her children’s potential for autonomy, they do not have permission to thrive without her consent and authorization. Her children are her property, and she is reluctant to share her property. Of course, proprietary preoccupations represent another form of egocentricity. She sees her children’s growth and maturity as a sign of rejection and an existential threat to the fragility of her tenuous selfhood (separation equals mental obliteration). If something positive happens to the children, it must include the mother, or it must be facilitated by the mother’s oversight and approval (no differentiation without representation). Begrudging behavior typically follows her tendency to pass judgment, whether explicitly or implicitly. Due to poor social cognition, the Borderline mother does not see her bulldozer-driven compulsion for interference and conceited sense of entitlement as inappropriate. When it comes to aggressive intrusion, it’s important to remember that boundaries of all types are anathema in dysfunctional families. Again and again, the family’s attention returns to the center stage of BPD predominance—held together by the clinging weight of propinquity.

The mother’s tendency towards jealousy and suspicion can result in blatant disapproval of her children’s acquaintances or accomplishments to displace her own insecurities and fear of abandonment. Likewise, BPD mothers often triangulate family members by means of favoritism, scapegoating, gossip, the silent treatment, criticism, shaming, derogatory humor, and forced allegiances. The mother will frequently alternate between praise (idealization) and criticism (devaluation) of her children according to the athleticism of their attentiveness. If guilt is habitually weaponized by the mother, it usually manifests by letting her children know how unappreciative they are of the sacrifices that were made for them. However, it’s often the case that many of these “sacrifices” were not requested by the child nor implemented to ensure success independent from the mother’s motivations. More often, these gestures represent a means of manipulating the child’s emotions by making them feel indebted and shamefully dependent because, let’s face it, they’re ultimately undeserving of any act of generosity that was originally denied to their mother. On some level, the mother knows how much she sacrificed as a child to appease her caregivers, so she feels that her family is obligated to emphatically acknowledge whatever she does for them. In response, her children may start feeling like Pavlov’s dog instead of feeling free to roam the yard. A BPD mother may complain about enabling her children, but what she’s really doing is enabling herself to assume martyrdom via virtue signaling. Tendentious charity implies that the provider should be praised and the receiver should be grateful. Instead of promoting sustainable independence and healthy self-esteem, the provider maintains power through resource allocation while the receiver remains disabled. Overindulgence of any ilk, and the accompanying language of sacrifice and atonement, eventually becomes a bargaining device to discourage betrayal.

According to Tom Bunn, LCSW: “She cannot tolerate feelings of abandonment. She must, no matter what it does to the child, cripple at least one child so that the child will never, even as an adult, be able to leave her. This means destroying at least one child’s ability to function as an independent person. The child must never outgrown the feeling of being a part of the mother.” Or, as Dr. James Masterson put it, “There is a belief by each of them that if one dies, the other will die. The concept of emotional blackmail is now visible, for if a child believes their very existence depends upon their mother’s existence, and is thus responsible for her life, how can they venture far from her? What if she should have health problems and her child is not there to save her?” In summation, the self-sufficiency and potential self-actualization of the child is supplanted by time-released idealization and occasional donations to prolong a cycle of guilt and dependency that has been engineered by the mother to satisfy her own needs, albeit unconsciously. The Cluster B exchange rate inevitably leaves a trail of bemused children who feel ambivalent about their prospects for acquiring self-efficacy. In families where money and possessions are the currency of love, it’s like putting a fresh coat of paint on a house that’s already been eaten by termites.

Borderline mothers cannot tolerate separation, and their overbearing presence can feel suffocating, intrusive, or “cannibalistic” to her children as they attempt to claim sovereignty in adulthood. The children are instrumentalized as props to stabilize their mother’s unstable emotions while also serving as sympathetic subordinates to soothe her all-encompassing anxieties. A BPD mother clips the wings of her children because her own wings are not stable enough for flying solo in the stratosphere of life’s daily challenges. Reality, in its messiness and incompatibility with her cognitive distortions, dysregulates the Borderline mother, so she creates what amounts to her own reality and defends it with the tenaciousness of a bull shark. Whenever her children provide reassurance and emotional support, their efforts are randomly rewarded through a process of variant ratio scheduling (inconsistent praise via intermittent positive reinforcement) to keep her children compliant. Being defined by the gaze of the other, her most deferential children conveniently serve as endemic sources of regulatory supply. BPD mothers do not teach their children self-respect; they teach their children to respect the needs of their mother. Her rejection sensitivity and paranoia keep her in a constant state of agitation while seeking reassurance for her cognitive distortions caused by impaired reality testing. Likewise, the desperate neediness of the mother is usually reinforced by the approval-seeking behavior of her children. The child is searching for a “good enough” mother, but the mother is also a child searching for a “good enough” mother. After all, what child doesn’t yearn for love and approval from their parents? However, children who have surrendered themselves for the sake of parental acceptance (being defined by the Borderline) will invariably become more codependent over time—sacrificing their potential for fulfillment as adults. In addition, the mother’s need for control can undermine her children’s ability to freely express themselves, feel confident, establish boundaries with others, or take initiative. As a result, her children will feel emotionally paralyzed, defensive, guilty, and helpless while deferring to their mother’s relentless crusade for supremacy, similar to what happens during Stockholm syndrome.

In many ways, children of BPD mothers are not allowed to grow up because growing up represents a threat to the mother’s need for safety. In this sticky situation, the emotional dependency and psychological immaturity of the mother is projected onto her children to make them feel dependent on her. The mother’s fear of abandonment is often so insurmountable that the very idea of her children establishing a life of their own is considered a threat to her survival. Consequently, becoming mollification marionettes is easier for the children than trying to untangle the complicated web of psychological strings that resulted in submission and regressive enmeshment. Torn between a tale of two incompatible identities, her children are expected to regress into a realm of infantilism while taking on selective parenting roles. Regression keeps the mother from feeling threatened by her children’s natural progression towards adulthood, and parentification allows for comfort when the mother is seeking consolation, special assistance, guidance, or reassurance for her worldview and life choices. Ironically, the mother may later blame her children for their continued dependence while simultaneously disapproving of her children’s efforts to individuate—it’s like trying to escape a mobius strip. In other words, the psychological health and independence of her children triggers the mother’s worst fear: relinquishing emotional dependency. Incentivizing enmeshment is how the codependent sausage is made.

The mask of normality (false self) is perhaps the most impressive adaptive mechanism of people with Borderline Personality Disorder—a Trojan Horse for social acceptance and protective facade that facilitates interpersonal functioning. A Borderline mother’s false self could be thought of as a “surrogate self” that substitutes for what could have been or what should have been (i.e., integrated/ true self). The false self, transactional and superficial as it is, also belies how much people with this disorder struggle inside. Because the Borderline mother inhabits a dissociative self due to a lack of intrapsychic congruency, she must construct a functional cover through presentation management that allows her to mask her shadow self. Although her skin is thin, it’s highly polished and adept at deflection. Being “perfectly presentable” to an invalidating and abusive parent ensured acceptance during childhood, but it prevented the authenticity of identity that develops through healthy exploration and secure attachment. Subsequently, most Borderline mothers have perfected the art of being perfectly presentable between periods of dysphoria or anger and can switch to smiles on a dime when the threat of embarrassment shows up at their front door. As mentioned in The Borderline Koan, people with BPD can go “under the radar” for extended periods of time by appearing composed, charming, vivacious, affectionate, generous, glamorous, and ostensibly reasonable to those who encounter them during brief interactions (the halo effect). In due course, the Borderline mother becomes an imposter who succumbs to self-deception before deceiving others with her constructed persona. In addition to her varnished mannerisms, the BPD mother earnestly tries to maintain an internalized “good object,” which may include feelings of moral superiority, impassioned convictions, and redemptive vanity to offset her internalized “bad object,” which tells her that she is unattractive, inadequate, stupid, and worthless. BPD virtue signaling, for example, is an elaborate announcement of moral rectitude to bolster the integrity of their tenuous sense of goodness, regardless of its proactive validity. This also explains the infamous mismatch between how people with this disorder want to be seen versus how they really feel and behave when their insecurities are triggered. To make matters worse, the mother is saddled with feelings of guilt and shame that she attempts to discharge onto the nearest recipient, as if they were grounding conductors for her internal lightning storm.

While compensatory structures allow people with BPD to function well in most settings, defensive structures keep them in a perpetual state of anxiety that inevitably results in conflict. More importantly, dissembling prevents exposure, because exposure means death to the Borderline’s alloplastic defense mechanisms. Mirroring (emulating the behavior of others and/or appropriating their interests) also keeps the BPD mother from feeling estranged during social gatherings or interactions with intimate others. However, the Borderline’s public image is usually quite different from their private persona, especially when their precarious mood begins to shift during encounters with frustration. Stress, perceived rejection, and feelings of being disrespected typically precede defensive behavior designed to protect the mother’s fragile sense of self. If interpersonal conditions do not remain auspicious, the mother’s hostility will take the wheel (some people with BPD have a ceiling to their animus and episodic rage, while others do not). Even more disturbing, a subset of BPD mothers can deteriorate into a state of transient psychosis or secondary psychopathy under severe stress, hence commentary about Borderlines appearing “possessed” when splitting occurs. What an untreated Borderline is capable of when their back is against the wall is not suitable for all audiences, but this is also how they maintain control over their spectators.

Being masters of theatrical performance (psychodrama) and blame-shifting, Borderline mothers often convince acquaintances and concerned others that their primary difficulties in life are caused by ungrateful children, lackluster partners, evildoers, and “those damn people” (fundamental attribution errors). After all, mothers suffering from this disorder experience their interpretations as correct and subsequent reactions as self-justified, regardless of how far the lens of their inner world deviates from an accurate assessment of the outer world. No matter how misaligned such thoughts, feelings, and reactions might appear from an objective perspective, most Borderline mothers will find a way to pass customs without undergoing a search and seizure of their psychological baggage. When desperation is cornered, the ingenuity of the escape artist can be stunning. To control the narrative is how the war of public relations is won. Poor object relations and impaired reality testing combine forces with a high index of suspicion as the mother’s list of persecutors escalate beyond the event horizon. If she can’t trust the vicissitudes of her own mind, how can she trust anyone who lives outside of it? To be sure, an untreated Borderline mother needs to be counterbalanced by an exceptionally healthy partner for her children to prosper, but anyone who is truly levelheaded either wouldn’t stick around for long or remain healthy. Parental alienation, for example, happens when the mother triangulates the children against her spouse, resulting in even more discontinuity among family members. Co-parenting collapses and the children are forced to pick sides without understanding the real source of disharmony. As the art of projection reaches a fevered pitch, the mother conveniently avoids accountability for her unreasonableness and behavioral inconsistencies via plausible deniability, self-justification, blame, and intimidation. Developing insight is an inside job that externalizing disorders are not inherently equipped to handle.

As a reminder, untreated people with BPD do not see themselves as disordered (anosognosia) and believe passionately that their thoughts, feelings, and reactions are entirely justified. Being chronically irrational, Borderline mothers rely on emotional reasoning rather than logic and confuse their children during communication through selective memory (dissociative amnesia), dismissiveness, anger, or complete denial (there are significant neuroanatomical and functional differences in the BPD brain that also account for these unwelcoming responses). In other words, the mother’s memory is biased towards information that avoids personal blame and feelings of shame (emotional memory blocking). Revisionism is a Borderline trademark, despite the magnitude of historical evidence to the contrary. Sitting with uncomfortable feelings is a job too great for those who prefer the safety of experiential avoidance. Whatever a person with BPD remembers during periods of conflict will always be someone else’s fault, because their hypersensitivity to mortification cannot tolerate the additional burden of developing insight or accepting accountability. Projection for questionable or impulsive behavior alleviates feelings of guilt and shame, and this bounces-off-of-me-and-sticks-to-you gambit is evident in brazen blame-shifting statements, such as, “Look at what you made me do!” Externalizing causation is the waxed jacket of Cluster B pathology, and every opportunity to point fingers increases its utility value during each rain storm. BPD mothers do not have the temperament, maturity, or attention span to engage in emotionally challenging conversations, and they will preemptively shut down discussions that might lead to questioning their thoughts or actions. Even when a particular conversation seems normal or productive, the following is sure to plummet. No matter how tempting, her children should never broach topics that will trigger their mother’s reactivity. The children’s repeated attempts to JADE (justify, argue, defend, and explain), no matter how articulate or reasonable, never work. In reality, the better the child is at explaining themselves, the less they’re understood. The nuances of rationality and independent thought are a threat to the emotional biases of the mother because disagreement equals rejection. As a result, she will often tune out during emotionally challenging discussions, which makes her children feel even more invalidated. Healthy communication is anathema to the Borderline mother because it triggers archaic fears associated with painful subject matter and threatens the adhesive strength of the trauma bond. Besides, even the most innocuous dialogue can be misinterpreted as confrontational commentary due to the mother’s keen sensitivity and her propensity for paranoia. In fact, some of the most protracted, profligate, and contentious conversations occur whenever children of the disordered try to extract order from their parent’s misconceptions, deflections, and bizarre digressions. Keeping things light and superficial is the only way to potentially avoid an avalanche of primitive defense mechanisms, and any discussion about the fact that mommy might be disordered typically backfires with a loud report (untreated people with BPD frequently feel offended rather than relieved by the suggestion that their symptoms stem from character disturbance, and this problem is undoubtedly made worse by the associated stigma surrounding Cluster B disorders). Unfortunately, the least effective people at convincing someone suffering from a personality disorder to seek specialized treatment are usually the individuals who are closest to them.

The Borderline mother’s lack of self-awareness is utterly astounding, but it’s a protective mechanism to avoid deep feelings of insecurity, self-loathing, guilt, and shame. Likewise, her abundant use of criticism and insults allows her to maintain a grandiose image to compensate for low self-worth via projection. Whatever is wrong, it can’t possibly have anything to do with her. In fact, the denial of the BPD mother can become so tenacious that her family lives in denial by proxy. In many ways, the mother’s full-time job is to convince herself and others that she is right about the nature of reality so that she can forever externalize whatever she is too afraid to acknowledge. However, never letting them see you sweat is the gateway to regret for families who embrace the alluring anesthetization of denialism.

“The mother may be blatantly ill, but more often her pathology is quite subtle. She may even be perceived by others as ‘the perfect mother’ because of her total ‘dedication’ to her children. Further observation, however, reveals her overinvolvement in her children’s lives, her encouragement of mutual dependencies, and her unwillingness to allow her children to mature and separate naturally,” states Jerold J. Kreisman, M.D.